Important Stops to Visit Along the Trail of Tears

Stretching nearly 5,000 miles through nine U.S. states, the Trail of Tears is more than a line on a map—it is a living scar etched into forests, riverbanks, and quiet town squares. Each bend preserves echoes of Cherokee laughter, Choctaw hymns, and the crunch of wagon wheels dragging futures westward. Today, roadside waysides and hidden forest paths invite travelers to stand where treaties were debated, prayers whispered, and resilience kindled. From Georgia’s abandoned capital at New Echota to Kentucky’s sandstone Mantle Rock arch, these stops turn history’s abstract tragedy into tangible ground beneath your boots, sparking reflection on loss and survival. These are some of the important stops to visit along the Trail of Tears.

The Museum of the Cherokee People, Cherokee, North Carolina

Located in Cherokee, North Carolina, The Museum of the Cherokee People stands as one of the nation’s oldest tribal museums, established in 1948. Situated within the Qualla Boundary—the sovereign land of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians—the museum offers an immersive journey through 11,000 years of Cherokee history and culture. Visitors can explore exhibits featuring ancient artifacts, traditional crafts, and contemporary works by Cherokee artists.

Interactive programs, such as demonstrations by Atsila Anotasgi Cultural Specialists, provide hands-on experiences in finger-weaving and basketry. The museum also honors Cherokee military service in the Charles George Beloved Veterans Hall. Recognized for its cultural preservation efforts, it received the 2022 Guardians of Culture and Lifeways International Award.

New Echota, Calhoun, Georgia

Once the Cherokee Nation’s capital, New Echota preserves the moment sovereignty met removal. Walk original streets linking the Council House, Supreme Court building, and the Cherokee Phoenix print shop—the first Native‑language newspaper in America.

Inside furnished cabins, voices from interpreters recount debates over the 1835 Treaty of New Echota that ceded ancestral homelands for distant territory. A nature trail skirts Town Creek, framing farmland the tribe fought to keep. Wayside plaques chronicle states’ oppressive laws, missionary resistance, and the divisive treaty faction. Standing here, you grasp both the brilliance of Cherokee self‑government and the heartbreak of its coerced surrender.

Chief Vann House, Chatsworth, Georgia

Built in 1804 by James Vann, a prominent Cherokee leader and businessman, The Chief Vann House was the first brick residence in the Cherokee Nation and earned the title “Showplace of the Cherokee Nation.” The mansion showcases exquisite hand-carved woodwork, a unique floating staircase, and original Federal-style architecture.

Visitors can explore the restored home and its grounds, gaining insight into the Vann family’s legacy and the broader Cherokee experience before their forced removal on the Trail of Tears.

Red Clay State Historic Park, Cleveland, Tennessee

Nestled among blue‑green ridges, Red Clay was the Cherokee Nation’s final council ground before forced exile. The centerpiece is a reconstructed council house encircling the Eternal Flame of Remembrance, symbolizing ancestral fires never extinguished. Nearby, the crystal‑clear Blue Hole Spring supplied thousands during tense 1832–1838 meetings where leaders weighed survival versus resistance.

Interpretive exhibits reveal how state encroachment and federal policy cornered the tribe, while a peaceful three‑mile boundary trail traverses meadows once lined with encampments. Today the Red Clay State Park hosts annual Cherokee cultural gatherings, echoing ancient songs across rolling hills where momentous decisions sealed a people’s fate.

Ross Landing (Chattanooga Riverfront), Tennessee

Modern Chattanooga’s vibrant riverwalk masks Ross Landing’s grim departure scene. In autumn 1838, John Ross’s detachment and others boarded flatboats here, beginning a perilous 650‑mile water route. Art installations mark original wharf pilings; interpretive kiosks juxtapose bustling steamboats with overcrowded removal crafts. A landscaped overlook frames Moccasin Bend, homeland fields confiscated for settlers.

Nearby, the Passage—a cascading fountain descending the bluff—commemorates each detachment through symbolic seven zodiac‑like columns. Evening projections of Cherokee faces animate misty walls, inviting reflection on resilience and loss amid nightlife that now fills warehouses once stacked with confiscated Cherokee goods.

The Charles Hall Museum and Heritage Center, Tellico Plains, Tennessee

As a National Park Service–certified site on the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, the Charles Hall Museum and Heritage Center preserves Native American, Appalachian, and local history, with a focus on the Greater Tellico Plains area.

The museum features over 10,000 artifacts, including Native American tools, military relics, antique telephones, and early Appalachian homesteading items. Interpretive panels detail the 1838 Cherokee Removal, during which over 3,000 Cherokee passed through the area. A garden and walking trail behind the museum trace fields once marked by Cherokee mounds.

Port Royal State Historic Park, Adams, Tennessee

Port Royal State Historic Park preserves a poignant chapter of American history. In late 1838, over 10,000 Cherokee camped here for the last time in Tennessee before crossing into Kentucky on the Trail of Tears. The park features a preserved 300-yard section of the original Trail of Tears route, certified by the National Park Service.

Visitors can explore interpretive trails, the historic 1890 Pratt truss bridge over Sulphur Fork Creek, and remnants of the 18th-century town, including stone foundations and the 1859 Masonic Lodge. These elements offer a tangible connection to the site’s layered past.

Manitou Cave of Alabama, Fort Payne, Alabama

Located in Fort Payne, the Manitou Cave holds profound significance in Cherokee history and the Trail of Tears. Situated near the former Cherokee town of Willstown, the cave features inscriptions in the Cherokee syllabary, likely made by Sequoyah’s son, documenting ceremonial events.

These inscriptions, found deep within the cave, underscore its role as a sacred space for the Cherokee people. During the 1830s, the area was a focal point of Cherokee life before the forced removal. Today, as a certified Trail of Tears National Historic Trail Interpretive Center, Manitou Cave offers guided tours by appointment, educating visitors about its historical and cultural importance.

Mantle Rock Preserve, Smithland, Kentucky

A secluded 387‑acre preserve shelters Kentucky’s largest natural sandstone arch, Mantle Rock, beneath which hundreds of Cherokees huddled during the brutal winter of 1838‑1839 awaiting a frozen Ohio River. A 2.8‑mile trail reveals preserved wagon ruts, lichen‑draped boulders, and rare wintergreen plants once foraged by starving families.

Interpretive signs share missionary Daniel S. Butrick’s despairing letters alongside survivor Rowena Kitts’s recollections of communal hymn‑singing echoing beneath the arch’s vaulted ceiling. Today the airy span frames tranquil woodland, offering space for reflection, birdwatching, and remembrance ceremonies held each January by Cherokee descendants retracing ancestral footsteps.

Trail of Tears Commemorative Park, Hopkinsville, Kentucky

Once a winter encampment along the Northern Route of the Trail of Tears, the Trail of Tears Commemorative Park holds the graves of Cherokee leaders Chief White Path and Fly Smith, who died here in 1838. A restored log cabin Heritage Center displays artifacts and exhibits detailing the Cherokee removal.

Visitors can explore walking paths with interpretive signs, a statue garden, and a flag memorial. The park also hosts an annual Intertribal Pow Wow, celebrating Native culture through dance, music, and crafts.

Paducah Waterfront, Paducah, Kentucky

Along the Ohio River in downtown Paducah, Kentucky, the waterfront marks a significant stop on the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail. In the winter of 1838–1839, four Cherokee detachments, including one led by Principal Chief John Ross, paused here to procure supplies during their forced relocation.

Today, interpretive signage near the floodwall entrance on South Water Street educates visitors about this somber chapter in American history. The site offers a place for reflection, connecting the present to the resilience and hardships of the Cherokee people during their journey westward.

Camp Ground Church, Anna, Illinois

In the winter of 1838–1839, the Camp Ground Cumberland Presbyterian Church near Anna, Illinois, served as a significant encampment site for over 3,000 Cherokee during their forced relocation along the Trail of Tears. The site’s natural springs and a gristmill provided essential resources for the weary travelers.

Tragically, many succumbed to the harsh conditions, and several Cherokee children are believed to be buried in unmarked graves within the adjacent cemetery. Today, the church and cemetery are recognized on the National Register of Historic Places, offering a solemn reminder of this dark chapter in American history.

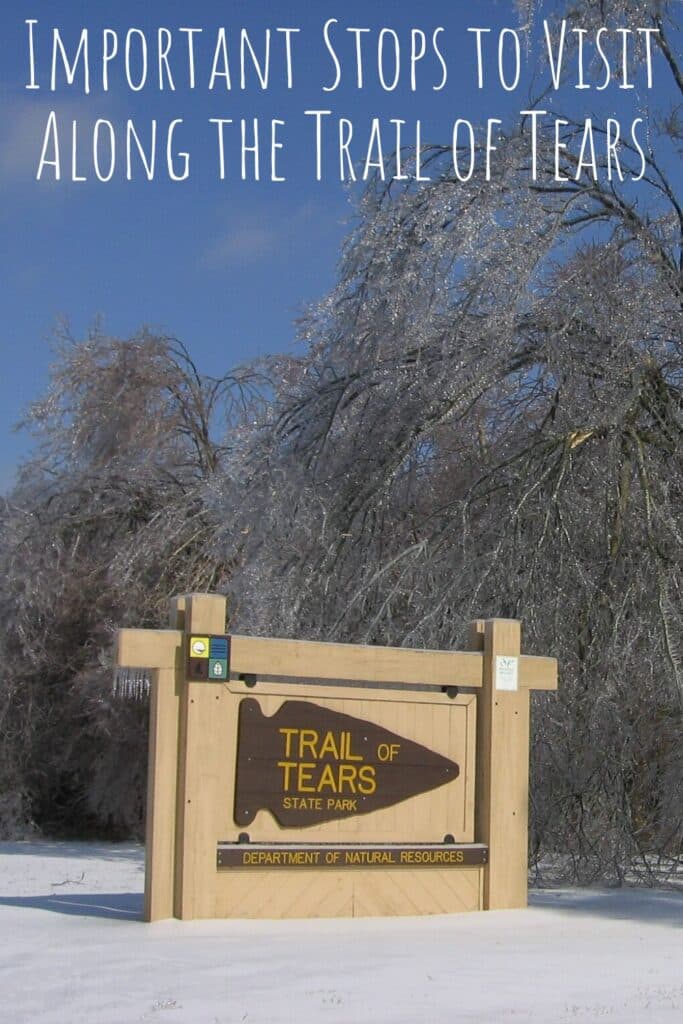

Trail of Tears State Park, Jackson, Missouri

Trail of Tears State Park in Jackson, Missouri, commemorates the forced relocation of the Cherokee people during the winter of 1838–1839. Nine of the thirteen Cherokee detachments crossed the Mississippi River at this location, enduring harsh winter conditions.

The park’s visitor center offers exhibits detailing this tragic chapter in American history, including a 23-minute documentary titled “Trail of Tears.” Visitors can explore hiking and horseback trails, enjoy fishing in the Mississippi River and Lake Boutin, and take in majestic views of the river. The park also features the Bushyhead Memorial, honoring those who perished during the journey.

Parkin Archeological State Park, Parkin, Arkansas

At Parkin, ancient Mississippian mound culture meets nineteenth‑century upheaval. The trail begins at a 17‑acre village site dating 1350–1650 CE, then overlays 1830s removal road used by Bell’s detachment. Museum displays juxtapose prehistoric pottery with Cherokee belongings recovered along the route.

Ranger‑led hikes describe how Indigenous peoples continuously adapted to change—from Hernando de Soto’s 1541 expedition to forced migration three centuries later. Riverfront boardwalks overlook the St. Francis River’s oxbows where weary travelers replenished supplies. Birds chorus above towering bald cypress, offering a serene counterpoint to stories of fever outbreaks and muddy axle‑deep ruts.

Village Creek State Park, Wynne, Arkansas

Quiet hardwood forests shield some of the Trail of Tears’ best‑preserved wagon ruts. Village Creek’s Old Military Road segment winds three miles, its twin swales sunk waist‑deep where thousands trudged westward. Interpretive signs identify wild persimmon and pawpaw trees that once supplemented meager corn rations.

The visitor center’s relief map traces diverging Northern and Bell routes converging nearby. Rent a bike or horse to traverse the shaded corridor, hearing woodpeckers echo like distant drumbeats. Evening campfire programs share first‑person accounts, while adjacent Lake Dunn offers respite—mirroring the exhaustion, grief, yet enduring hope travelers carried onward.

Pea Ridge National Military Park, Garfield, Arkansas

Better known for its 1862 Civil War clash, Pea Ridge also safeguards an untouched mile of Benge Route along the Trail of Tears. A mowed “historic trace” parallels the loop drive, letting visitors walk where Cherokee families once trudged westward.

Ranger programs highlight journal entries by Dr. Elijah Hicks, detailing hardships like ice storms and illness. Interpretive signs link the Cherokee Removal to later Civil War battles fought along the same path, revealing layers of conflict and displacement.

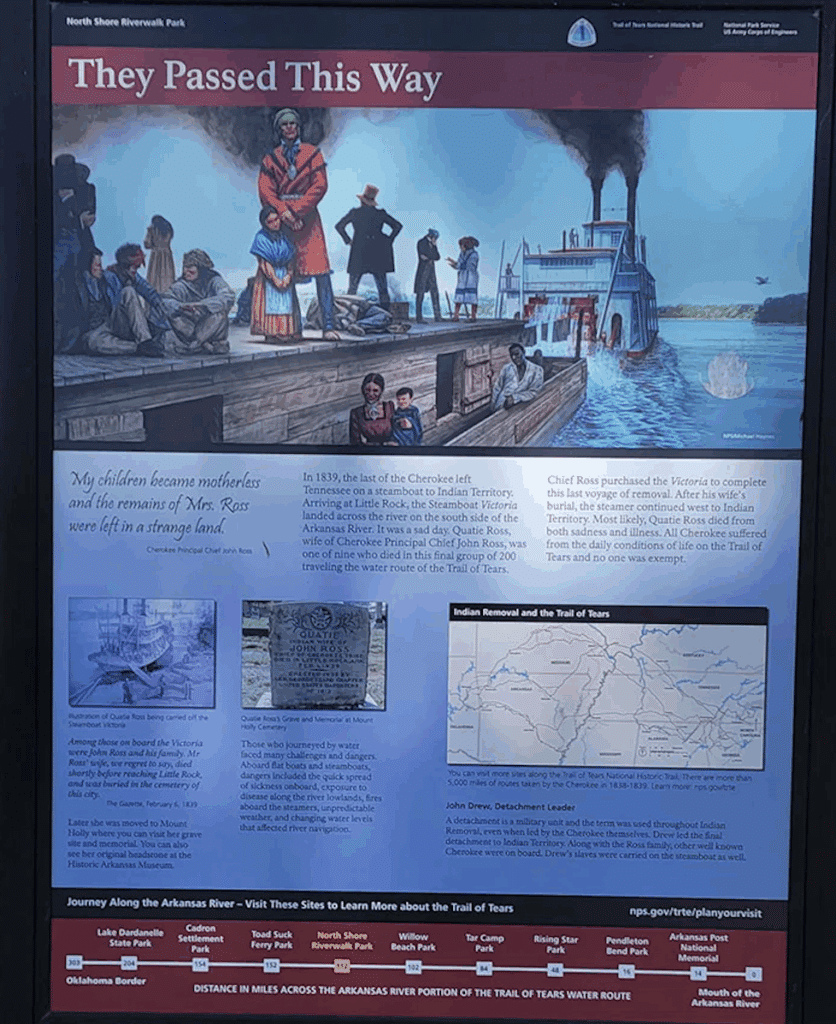

North Shore Riverwalk Park in North Little Rock, Arkansas

Situated along the Arkansas River, the North Shore Riverwalk serves as a poignant reminder of the Trail of Tears, featuring interpretive panels that commemorate the forced relocation of Native American tribes, including the Cherokee, Choctaw, Muscogee, Chickasaw, and Seminole, during the 1830s and 1840s.

These exhibits highlight the significance of the Arkansas River as a water route for the Cherokee, with detachments traveling westward to Indian Territory. The park offers a space for reflection on this tragic chapter in American history.

Shiloh Museum of Ozark History, Springdale, Arkansas

The Shiloh Museum of Ozark History in Springdale, Arkansas, is situated along the historic Old Wire Road, a route traversed by Cherokee detachments during their forced relocation in the 1830s. The museum’s exhibits delve into the experiences of the Cherokee people during the Trail of Tears, highlighting the challenges they faced and the impact on the Ozarks region. As a certified site on the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, the museum offers visitors a chance to learn about this significant chapter in American history.

Hunter’s Home, Park Hill, Oklahoma

Built in 1845 by George Murrell, Hunter’s Home in Park Hill, Oklahoma stands as the only remaining antebellum plantation home in the state. Murrell, a Virginia-born merchant, relocated with his Cherokee wife, Minerva Ross—niece of Chief John Ross—during the Trail of Tears. The estate reflects the resilience of the Cherokee Nation as they rebuilt their lives in Indian Territory. Today, as a certified site on the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, Hunter’s Home offers visitors a glimpse into 19th-century Cherokee life through preserved architecture and living history demonstrations.

Sequoyah’s Cabin Museum, Sallisaw, Oklahoma

Log walls hewn in 1829 house the genius who created the Cherokee syllabary. After surviving removal, Sequoyah resettled here, promoting literacy that unified dispersed people. Today a glass‑encased structure safeguards the Sequoyah’s cabin, preserving interior hearth, bedstead, and trade tools. Exhibits display rare hand‑printed Cherokee Bibles and Sequoyah’s silver plant‑name labels.

Surrounding gardens cultivate corn, beans, and tobacco varieties documented in his notes. Audio stations share descendants’ memories of storytelling sessions by firelight. Visiting underscores how cultural innovation thrived even after displacement, transforming grief into empowerment through written language cherished worldwide.

Cherokee National History Museum, Tahlequah, Oklahoma

Housed in the historic Cherokee National Capitol building in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, the Cherokee National History Museum offers an immersive journey through the Cherokee people’s history, including their forced removal during the Trail of Tears.

Through artifacts, interactive exhibits, and augmented reality presentations, visitors gain insight into the hardships endured during the 1830s relocation and the resilience of the Cherokee Nation. The museum, a certified site on the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, stands as a testament to the enduring spirit and cultural heritage of the Cherokee people.

Each stop along the Trail of Tears bears witness to the strength, suffering, and survival of the Native peoples who endured unimaginable hardship. Visiting these sites offers a chance not only to honor their memory, but to deepen our understanding of a history that still echoes today.